, p475](/reflexions/generative_models/end_autoregressive_models/density_models.png) Therefore, other methods have emerged that are more "data-driven", which do not require full model specification from the start but focus solely on the data

(with few to no assumptions about the function to be learned to represent the data).

One of these methods for generative modeling is the Energy-Based modeling

. Energy-Based models flexibly model probability distributions

and have risen in popularity recently thanks to the impressive results obtained in image generation by parameterizing the distribution with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN).

Model the data distribution: first step of generative modeling

Learning statistical models of observational data has always been one of the primary goals in machine learning and more generally in statistics.

Density models

Density models are models that learn the probability density function (PDF) $ p_θ $ of the data, assuming that the data follows a probability density function.

Why using density functions to describe the data? Because density functions provide a mathematically rigorous way to describe the distribution of continuous random variables.

Density functions are normalized, meaning the total probability over all possible outcomes is 1: Density functions give high values to regions where there is lot of observed data, and low values to regions where there is few or no observed data, since it is a probability (sum of all values equal to 1).

This ensures that the probabilities are meaningful and consistent.

Energy-Based Models

Energy-Based Models emerged to tackle the assumption that the function to be learned is normalizable (because it is not always the case)

. Energy-Based Models exploit probability distributions only defined though unnormalized scores.

The approach is still to find $ p'_θ $ which we think is a good approximation of the real data distribution. Since $ p'_θ $ is unnormalized, $ p_θ(x) = p'_θ(x) / Z_θ $, so it is easy to go back to a normalized density function

(we just need to multiply by $ Z_θ $). This is why energy functions can do most of what probability densities can do (mathematically speaking), except that they do not give normalized probabilities.

In Energy-Based Models, $ p'_θ(x) = e^{-E_θ(x)}$, and $ E_θ $ is what we call the energy function

. $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ associates a scalar measure of incompatibility to each data point.

The $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ distribution comes from statistical physics

: Considering physical systems containing multiple particles, with a specific temperature, each particle has an energy associated with itself (kinetic energy, which is related to the movement of the particle, and potential energy, which is related to the interactions between the particles or with external fields).

The Boltzmann-Gibbs probability distribution describes the likelihood of a system being in a particular state based on the total energy of that state (of all particules) and the temperature of the system

. In this context, the state $ x $ of a system refers to a specific configuration of the positions of all particles within the system. For example, if we have $ n $ particles, then $ x $ is a vector $ [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n] $, where each $ x_i $ represents the position of the $ i $-th particle.

The energy $ E(x) $ of this state is a function of the positions of all particles.

The Boltzmann-Gibbs distribution $ p(x) $, providing the probability that the system is in a specific configuration $ x $, is given by the formula: \( p(x) = \frac{\exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\}}{Z} \)

where $ T$ is the temperature of the system, and \( Z = \int_{X^2} \exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\} dx \) is a normalizing constant that makes the distribution sum to one.

The probability $ p(x) $ describes the relative frequency at which the system is found in the state $ x $

. If we suppose that x is a one-dimensional state:

If we take a low temperature ( $ T = 1.6 $ ), we get:

Note that the normalized density is $ p(x) $. We see that states with lower energy $ E(x) $ are more probable, especially at low temperatures. Conversely, higher energy states are less probable.

Energy values reacts on the opposite of the density points: in probability density, there is a high value where there are lot of data and a low value where there is few data. It is actually the opposite for energy values: Lower energy values correspond to higher probability (more likely) data points, while higher energy values correspond to lower probability (less likely) data points

.

$ E_θ $ is actually part of the normalized density formula (it is part of the exponential form of the probability density function): \( p_\theta = e^{-\frac{E_\theta}{Z(\theta)}} \) where $ Z(θ) $ is the normalizing constant: \( Z(\theta) = \int_x e^{-E_\theta(x)} \, dx \)

.

Comparison of the loss and gradient formula

**The Kullback-Leibler (KL) loss : maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data**

use the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence as loss function

(to measure the distance between $ p_θ $ and $ p_{data} $): \( \arg \min_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}} \left[ -\log \frac{p_\theta(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x)} \right] = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_{\text{data}}(x)] \) \( = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] \) (since the second term has no dependence on $ p_θ $), which is almost equal to \( \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \log(p_\theta(x_i)) \), which is the maximum likelihood formula.

Therefore, it boils down to a form of maximum likelihood learning: the process of fitting the model to the data involves maximizing the likelihood of the observed data under the model (adjusting the parameters of the model so that it assigns the highest possible probability to the training data).

Let us see what happens when we try to learn the parameters of a model with maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data.

**1) For an Density Model:**

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

For a probability density function \( p_\theta(x) \):

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

Computing the gradient gives:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta \log p_\theta(x)]

\]

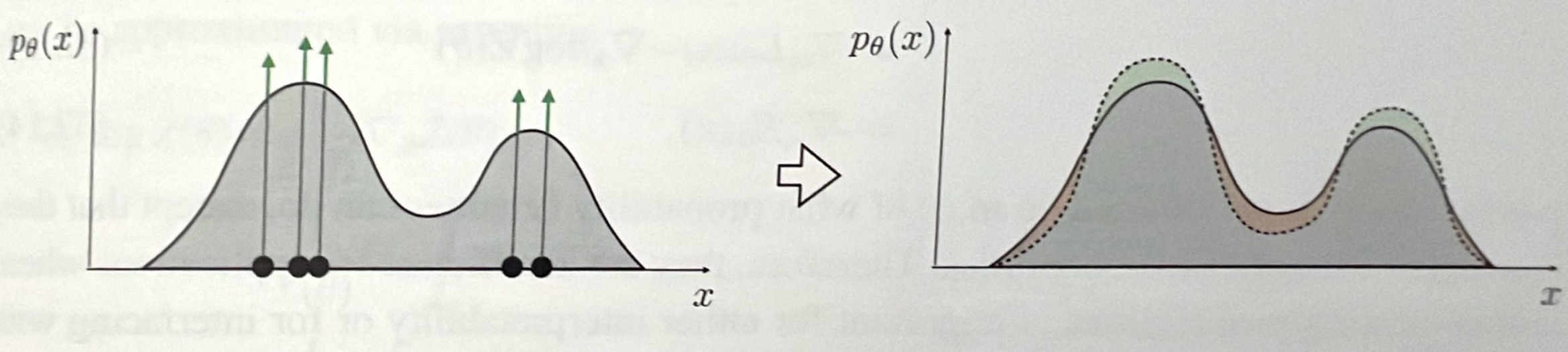

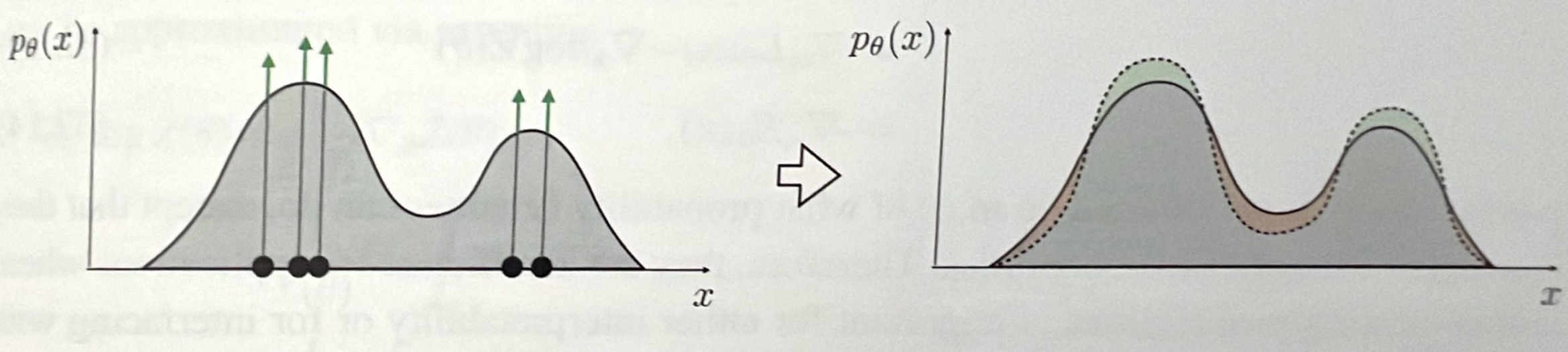

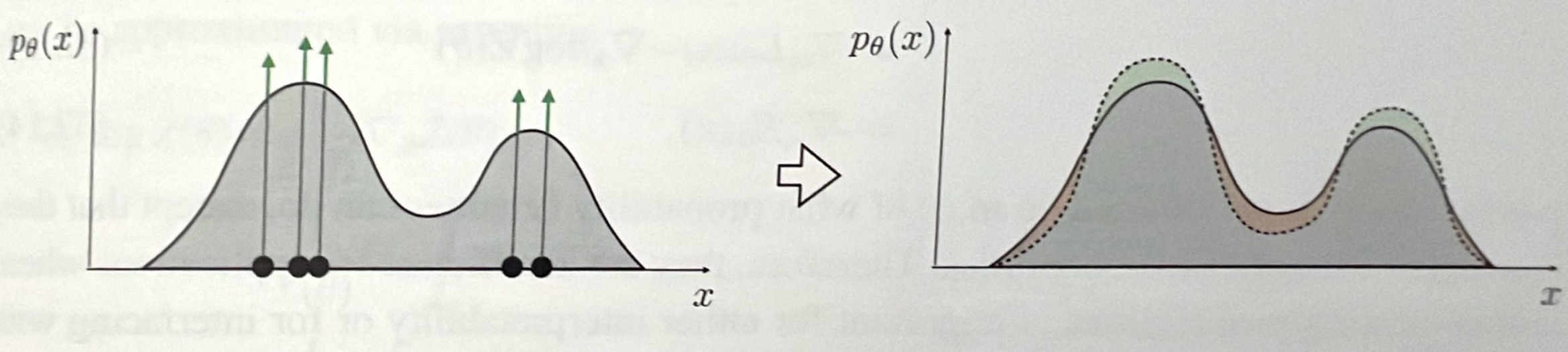

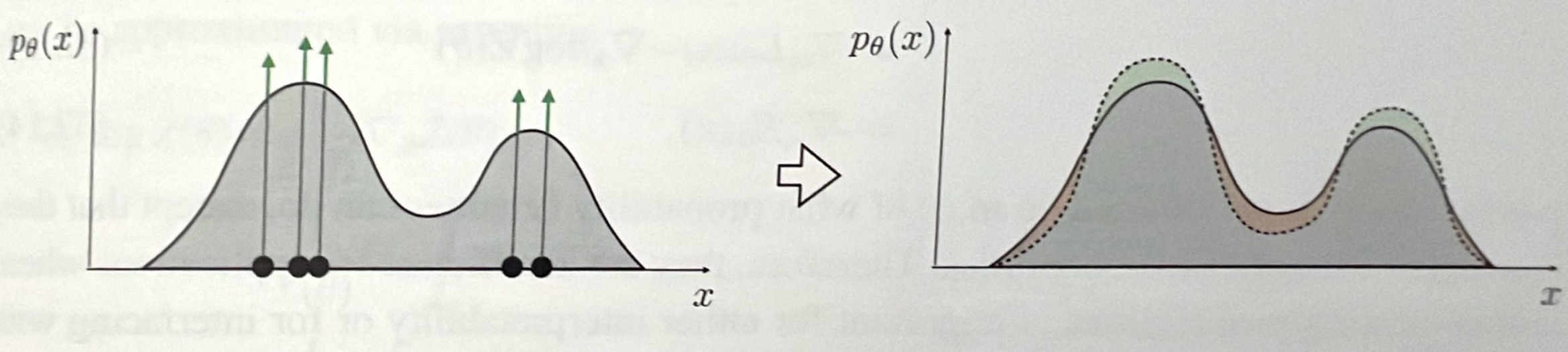

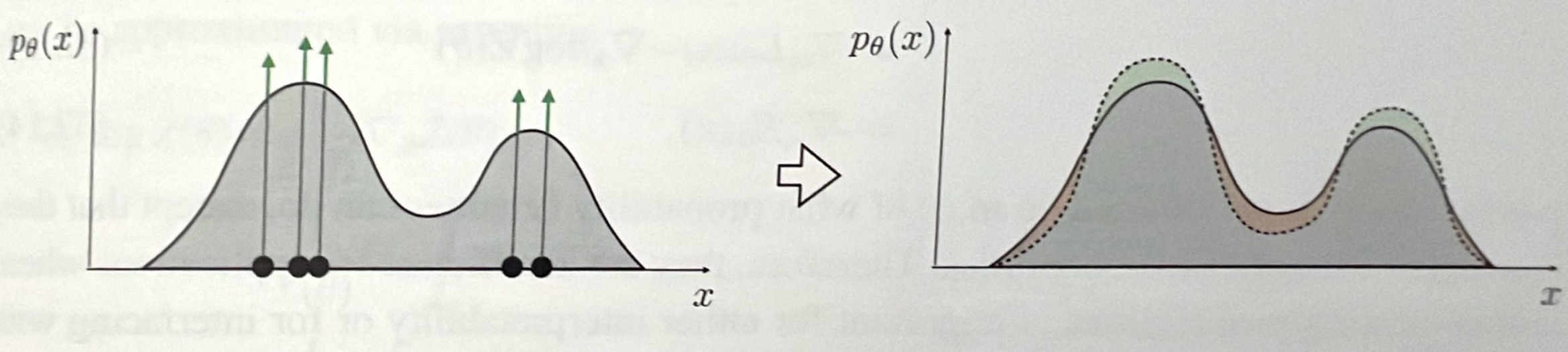

It comes down to pushing up the density over certain datapoints as presented in the figure in green

), we are forced to sacrifice the density over other regions

and pushing down the density over other datapoints as presented in the figure in red

:

*Fitting a max likelihood density model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p475*

**2) For an Energy-Based Model:**

For an Energy-Based Model (EBM), the probability density is often expressed in terms of an energy function $ E_\theta(x) $:

\[

p_\theta(x) = \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta}

\]

where \( Z_\theta \) is the partition function:

\[

Z_\theta = \int e^{-E_\theta(x')} dx'

\]

Thus, the negative log-likelihood becomes:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)] = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} \left[ \log \left( \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \right) \right]

\]

Simplifying this, we get:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [E_\theta(x)] + \log Z_\theta

\]

Computing the gradient of this function:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] + \nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta

\]

The second term can be rewritten as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = \frac{\nabla_\theta Z_\theta}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\nabla_\theta \int e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int \nabla_\theta e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int e^{-E_\theta(x)} \nabla_\theta (-E_\theta(x)) dx}{Z_\theta} = -\int \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x) dx

\]

Thus,

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = -\mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

Therefore, we can write the learning gradient as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

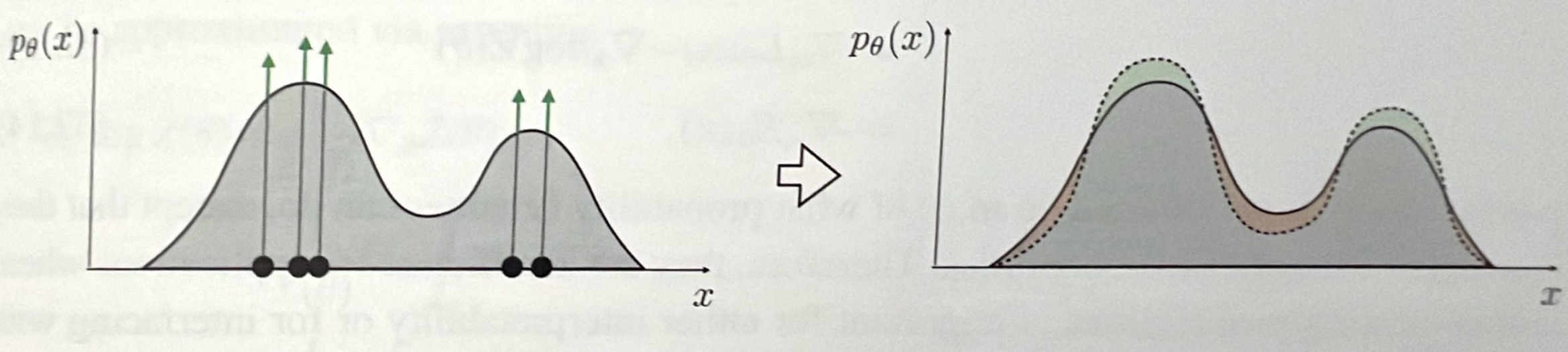

We can separate the loss into two phases of learning called positive and negative

. The positive phase consists of minimizing the energy of points drawn from $ p_{data} $

and is straightforward to compute assuming that $ E_θ(x) $ is differentiable (like a CNN). This has the effect of making the data points more likely (i.e., push down on their energy). However, this alone would lead to a flat energy landscape (i.e., 0 everywhere).

To counteract this, the negative phase pushes up on the energy of points drawn from the model distribution $ p_θ $

: the energy of the points that are unlikely in $ p_{data} $ will only get pushed up while those that are likely are going to get balanced out by the positive phase and will stay relatively low. It is the balancing of these two forces that shapes the energy landscape:

*Fitting a max likelihood energy model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p476*

Step2 of generative modeling: generate new data that fit the original data distribution

Once we have a model that correctly models the data distribution, we can generate new ”imagined” data points by starting a sampling chain at a random point (i.e. random noise for images) and let it drop to a low-energy point (i.e. an image most alike training data) or to high probability points

.

Generative models operate in a "one-to-many

" fashion, meaning that a single input can lead to multiple possible outputs. For example, if you input the same sentence into a text generation model, it could generate several different responses. So there is no single correct or predetermined answer for a given input. This introduces uncertainty that needs to be handled.

Thus, the generator must be stochastic

, meaning that it should incorporate elements of randomness. Thus, for the same input, a stochastic generator can produce different outputs each time it is executed. So we do not only need to build a generator that fit the original data distribution, but we also need to build a stochastic generator. How to do so?

- **The Diffusion models way:** A common method to make a stochastic generator is by using stochastic inputs

. This means that while the function itself is deterministic (producing the same output for the same input), it can produce varied results if the input is random. In other words, the generator would be $ generator(z, y) = x $ with $ z $ a randomized vector. In the case of image generation, if we give the generator as input "dog", it will generate an image of a dog, and this latent vector $ z $ will specify exactly which dog to generate

(breed, size, color, background, ...). $ z $ is called a "vector of latent variables" because the variables are not directly observed in the training data (it is also called "noise").

The function can output a different image $ x $ for each different setting of $ z $. Usually, we draw $ z $ from a simple distribution of Gaussian noise, that is, $ z∼N(0,1) $. $ G: Z, Y → X $

- **The Transformers way:** Transformers use the temperature parameter

or other sampling-based techniques

to manage ambiguity in text generation. The next token prediction in Autoregressive Transformers models is inherently a deterministic function; the same probability is assigned to the next tokens. During inference, greedy decoding (choosing the token with the highest probability at each step) keeps no randomness, whereas using sampling-based techniques like top-k sampling or nucleus (top-p) sampling, tokens are chosen randomly according to their probabilities, introducing randomness

into the generation process. The Temperature parameter scaling can also introduce stochasticity by altering the model's probability distribution over the next token.

I have based my writings on my comprehension of

*[Foundations of Computer Vision book from Antonio Torralba et al.](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), [Léo Gagnon et al's paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.12176) and [Andy Jones's post](https://andrewcharlesjones.github.io/journal/ebms.html)*

Therefore, other methods have emerged that are more "data-driven", which do not require full model specification from the start but focus solely on the data

(with few to no assumptions about the function to be learned to represent the data).

One of these methods for generative modeling is the Energy-Based modeling

. Energy-Based models flexibly model probability distributions

and have risen in popularity recently thanks to the impressive results obtained in image generation by parameterizing the distribution with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN).

Model the data distribution: first step of generative modeling

Learning statistical models of observational data has always been one of the primary goals in machine learning and more generally in statistics.

Density models

Density models are models that learn the probability density function (PDF) $ p_θ $ of the data, assuming that the data follows a probability density function.

Why using density functions to describe the data? Because density functions provide a mathematically rigorous way to describe the distribution of continuous random variables.

Density functions are normalized, meaning the total probability over all possible outcomes is 1: Density functions give high values to regions where there is lot of observed data, and low values to regions where there is few or no observed data, since it is a probability (sum of all values equal to 1).

This ensures that the probabilities are meaningful and consistent.

Energy-Based Models

Energy-Based Models emerged to tackle the assumption that the function to be learned is normalizable (because it is not always the case)

. Energy-Based Models exploit probability distributions only defined though unnormalized scores.

The approach is still to find $ p'_θ $ which we think is a good approximation of the real data distribution. Since $ p'_θ $ is unnormalized, $ p_θ(x) = p'_θ(x) / Z_θ $, so it is easy to go back to a normalized density function

(we just need to multiply by $ Z_θ $). This is why energy functions can do most of what probability densities can do (mathematically speaking), except that they do not give normalized probabilities.

In Energy-Based Models, $ p'_θ(x) = e^{-E_θ(x)}$, and $ E_θ $ is what we call the energy function

. $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ associates a scalar measure of incompatibility to each data point.

The $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ distribution comes from statistical physics

: Considering physical systems containing multiple particles, with a specific temperature, each particle has an energy associated with itself (kinetic energy, which is related to the movement of the particle, and potential energy, which is related to the interactions between the particles or with external fields).

The Boltzmann-Gibbs probability distribution describes the likelihood of a system being in a particular state based on the total energy of that state (of all particules) and the temperature of the system

. In this context, the state $ x $ of a system refers to a specific configuration of the positions of all particles within the system. For example, if we have $ n $ particles, then $ x $ is a vector $ [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n] $, where each $ x_i $ represents the position of the $ i $-th particle.

The energy $ E(x) $ of this state is a function of the positions of all particles.

The Boltzmann-Gibbs distribution $ p(x) $, providing the probability that the system is in a specific configuration $ x $, is given by the formula: \( p(x) = \frac{\exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\}}{Z} \)

where $ T$ is the temperature of the system, and \( Z = \int_{X^2} \exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\} dx \) is a normalizing constant that makes the distribution sum to one.

The probability $ p(x) $ describes the relative frequency at which the system is found in the state $ x $

. If we suppose that x is a one-dimensional state:

If we take a low temperature ( $ T = 1.6 $ ), we get:

Note that the normalized density is $ p(x) $. We see that states with lower energy $ E(x) $ are more probable, especially at low temperatures. Conversely, higher energy states are less probable.

Energy values reacts on the opposite of the density points: in probability density, there is a high value where there are lot of data and a low value where there is few data. It is actually the opposite for energy values: Lower energy values correspond to higher probability (more likely) data points, while higher energy values correspond to lower probability (less likely) data points

.

$ E_θ $ is actually part of the normalized density formula (it is part of the exponential form of the probability density function): \( p_\theta = e^{-\frac{E_\theta}{Z(\theta)}} \) where $ Z(θ) $ is the normalizing constant: \( Z(\theta) = \int_x e^{-E_\theta(x)} \, dx \)

.

Comparison of the loss and gradient formula

**The Kullback-Leibler (KL) loss : maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data**

use the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence as loss function

(to measure the distance between $ p_θ $ and $ p_{data} $): \( \arg \min_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}} \left[ -\log \frac{p_\theta(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x)} \right] = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_{\text{data}}(x)] \) \( = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] \) (since the second term has no dependence on $ p_θ $), which is almost equal to \( \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \log(p_\theta(x_i)) \), which is the maximum likelihood formula.

Therefore, it boils down to a form of maximum likelihood learning: the process of fitting the model to the data involves maximizing the likelihood of the observed data under the model (adjusting the parameters of the model so that it assigns the highest possible probability to the training data).

Let us see what happens when we try to learn the parameters of a model with maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data.

**1) For an Density Model:**

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

For a probability density function \( p_\theta(x) \):

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

Computing the gradient gives:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta \log p_\theta(x)]

\]

It comes down to pushing up the density over certain datapoints as presented in the figure in green

), we are forced to sacrifice the density over other regions

and pushing down the density over other datapoints as presented in the figure in red

:

*Fitting a max likelihood density model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p475*

**2) For an Energy-Based Model:**

For an Energy-Based Model (EBM), the probability density is often expressed in terms of an energy function $ E_\theta(x) $:

\[

p_\theta(x) = \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta}

\]

where \( Z_\theta \) is the partition function:

\[

Z_\theta = \int e^{-E_\theta(x')} dx'

\]

Thus, the negative log-likelihood becomes:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)] = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} \left[ \log \left( \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \right) \right]

\]

Simplifying this, we get:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [E_\theta(x)] + \log Z_\theta

\]

Computing the gradient of this function:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] + \nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta

\]

The second term can be rewritten as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = \frac{\nabla_\theta Z_\theta}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\nabla_\theta \int e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int \nabla_\theta e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int e^{-E_\theta(x)} \nabla_\theta (-E_\theta(x)) dx}{Z_\theta} = -\int \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x) dx

\]

Thus,

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = -\mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

Therefore, we can write the learning gradient as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

We can separate the loss into two phases of learning called positive and negative

. The positive phase consists of minimizing the energy of points drawn from $ p_{data} $

and is straightforward to compute assuming that $ E_θ(x) $ is differentiable (like a CNN). This has the effect of making the data points more likely (i.e., push down on their energy). However, this alone would lead to a flat energy landscape (i.e., 0 everywhere).

To counteract this, the negative phase pushes up on the energy of points drawn from the model distribution $ p_θ $

: the energy of the points that are unlikely in $ p_{data} $ will only get pushed up while those that are likely are going to get balanced out by the positive phase and will stay relatively low. It is the balancing of these two forces that shapes the energy landscape:

*Fitting a max likelihood energy model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p476*

Step2 of generative modeling: generate new data that fit the original data distribution

Once we have a model that correctly models the data distribution, we can generate new ”imagined” data points by starting a sampling chain at a random point (i.e. random noise for images) and let it drop to a low-energy point (i.e. an image most alike training data) or to high probability points

.

Generative models operate in a "one-to-many

" fashion, meaning that a single input can lead to multiple possible outputs. For example, if you input the same sentence into a text generation model, it could generate several different responses. So there is no single correct or predetermined answer for a given input. This introduces uncertainty that needs to be handled.

Thus, the generator must be stochastic

, meaning that it should incorporate elements of randomness. Thus, for the same input, a stochastic generator can produce different outputs each time it is executed. So we do not only need to build a generator that fit the original data distribution, but we also need to build a stochastic generator. How to do so?

- **The Diffusion models way:** A common method to make a stochastic generator is by using stochastic inputs

. This means that while the function itself is deterministic (producing the same output for the same input), it can produce varied results if the input is random. In other words, the generator would be $ generator(z, y) = x $ with $ z $ a randomized vector. In the case of image generation, if we give the generator as input "dog", it will generate an image of a dog, and this latent vector $ z $ will specify exactly which dog to generate

(breed, size, color, background, ...). $ z $ is called a "vector of latent variables" because the variables are not directly observed in the training data (it is also called "noise").

The function can output a different image $ x $ for each different setting of $ z $. Usually, we draw $ z $ from a simple distribution of Gaussian noise, that is, $ z∼N(0,1) $. $ G: Z, Y → X $

- **The Transformers way:** Transformers use the temperature parameter

or other sampling-based techniques

to manage ambiguity in text generation. The next token prediction in Autoregressive Transformers models is inherently a deterministic function; the same probability is assigned to the next tokens. During inference, greedy decoding (choosing the token with the highest probability at each step) keeps no randomness, whereas using sampling-based techniques like top-k sampling or nucleus (top-p) sampling, tokens are chosen randomly according to their probabilities, introducing randomness

into the generation process. The Temperature parameter scaling can also introduce stochasticity by altering the model's probability distribution over the next token.

I have based my writings on my comprehension of

*[Foundations of Computer Vision book from Antonio Torralba et al.](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), [Léo Gagnon et al's paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.12176) and [Andy Jones's post](https://andrewcharlesjones.github.io/journal/ebms.html)*

The limits and future of generative models

A generative model is a model which is designed to generate new data samples from learned data

. So a first step in generative modeling is to model the data distribution

(train a model that learns the data distribution) and a second step is to generate new data that fit that distribution

.

Introduction

Most of the current generative models we currently use (for image, text, video, sound, and any other data type generation) are not flexible in the way they model the data distribution : they assume that the function to be learned is normalized (probability which sums to 1),

which might be a false assumption over some data distribution.

We are not talking here about the architecture of the generative models (transformers, cnn, etc), but the way those architectures are parametrized during training

(ie the way the weights are modified in the backpropagation process of the training process). Indeed, in current generative models (which are density models), when the some weights are modified in the backpropagation process (like pushing up the density over certain datapoints as presented in the figure in green

), we are forced to sacrifice the density over other regions

(pushing down the density over other datapoints as presented in the figure in red

), because the function is supposed to be normalized (probability which sums to 1)

:

, p475](/reflexions/generative_models/end_autoregressive_models/density_models.png) Therefore, other methods have emerged that are more "data-driven", which do not require full model specification from the start but focus solely on the data

(with few to no assumptions about the function to be learned to represent the data).

One of these methods for generative modeling is the Energy-Based modeling

. Energy-Based models flexibly model probability distributions

and have risen in popularity recently thanks to the impressive results obtained in image generation by parameterizing the distribution with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN).

Model the data distribution: first step of generative modeling

Learning statistical models of observational data has always been one of the primary goals in machine learning and more generally in statistics.

Density models

Density models are models that learn the probability density function (PDF) $ p_θ $ of the data, assuming that the data follows a probability density function.

Why using density functions to describe the data? Because density functions provide a mathematically rigorous way to describe the distribution of continuous random variables.

Density functions are normalized, meaning the total probability over all possible outcomes is 1: Density functions give high values to regions where there is lot of observed data, and low values to regions where there is few or no observed data, since it is a probability (sum of all values equal to 1).

This ensures that the probabilities are meaningful and consistent.

Energy-Based Models

Energy-Based Models emerged to tackle the assumption that the function to be learned is normalizable (because it is not always the case)

. Energy-Based Models exploit probability distributions only defined though unnormalized scores.

The approach is still to find $ p'_θ $ which we think is a good approximation of the real data distribution. Since $ p'_θ $ is unnormalized, $ p_θ(x) = p'_θ(x) / Z_θ $, so it is easy to go back to a normalized density function

(we just need to multiply by $ Z_θ $). This is why energy functions can do most of what probability densities can do (mathematically speaking), except that they do not give normalized probabilities.

In Energy-Based Models, $ p'_θ(x) = e^{-E_θ(x)}$, and $ E_θ $ is what we call the energy function

. $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ associates a scalar measure of incompatibility to each data point.

The $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ distribution comes from statistical physics

: Considering physical systems containing multiple particles, with a specific temperature, each particle has an energy associated with itself (kinetic energy, which is related to the movement of the particle, and potential energy, which is related to the interactions between the particles or with external fields).

The Boltzmann-Gibbs probability distribution describes the likelihood of a system being in a particular state based on the total energy of that state (of all particules) and the temperature of the system

. In this context, the state $ x $ of a system refers to a specific configuration of the positions of all particles within the system. For example, if we have $ n $ particles, then $ x $ is a vector $ [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n] $, where each $ x_i $ represents the position of the $ i $-th particle.

The energy $ E(x) $ of this state is a function of the positions of all particles.

The Boltzmann-Gibbs distribution $ p(x) $, providing the probability that the system is in a specific configuration $ x $, is given by the formula: \( p(x) = \frac{\exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\}}{Z} \)

where $ T$ is the temperature of the system, and \( Z = \int_{X^2} \exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\} dx \) is a normalizing constant that makes the distribution sum to one.

The probability $ p(x) $ describes the relative frequency at which the system is found in the state $ x $

. If we suppose that x is a one-dimensional state:

If we take a low temperature ( $ T = 1.6 $ ), we get:

Note that the normalized density is $ p(x) $. We see that states with lower energy $ E(x) $ are more probable, especially at low temperatures. Conversely, higher energy states are less probable.

Energy values reacts on the opposite of the density points: in probability density, there is a high value where there are lot of data and a low value where there is few data. It is actually the opposite for energy values: Lower energy values correspond to higher probability (more likely) data points, while higher energy values correspond to lower probability (less likely) data points

.

$ E_θ $ is actually part of the normalized density formula (it is part of the exponential form of the probability density function): \( p_\theta = e^{-\frac{E_\theta}{Z(\theta)}} \) where $ Z(θ) $ is the normalizing constant: \( Z(\theta) = \int_x e^{-E_\theta(x)} \, dx \)

.

Comparison of the loss and gradient formula

**The Kullback-Leibler (KL) loss : maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data**

use the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence as loss function

(to measure the distance between $ p_θ $ and $ p_{data} $): \( \arg \min_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}} \left[ -\log \frac{p_\theta(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x)} \right] = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_{\text{data}}(x)] \) \( = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] \) (since the second term has no dependence on $ p_θ $), which is almost equal to \( \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \log(p_\theta(x_i)) \), which is the maximum likelihood formula.

Therefore, it boils down to a form of maximum likelihood learning: the process of fitting the model to the data involves maximizing the likelihood of the observed data under the model (adjusting the parameters of the model so that it assigns the highest possible probability to the training data).

Let us see what happens when we try to learn the parameters of a model with maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data.

**1) For an Density Model:**

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

For a probability density function \( p_\theta(x) \):

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

Computing the gradient gives:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta \log p_\theta(x)]

\]

It comes down to pushing up the density over certain datapoints as presented in the figure in green

), we are forced to sacrifice the density over other regions

and pushing down the density over other datapoints as presented in the figure in red

:

*Fitting a max likelihood density model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p475*

**2) For an Energy-Based Model:**

For an Energy-Based Model (EBM), the probability density is often expressed in terms of an energy function $ E_\theta(x) $:

\[

p_\theta(x) = \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta}

\]

where \( Z_\theta \) is the partition function:

\[

Z_\theta = \int e^{-E_\theta(x')} dx'

\]

Thus, the negative log-likelihood becomes:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)] = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} \left[ \log \left( \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \right) \right]

\]

Simplifying this, we get:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [E_\theta(x)] + \log Z_\theta

\]

Computing the gradient of this function:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] + \nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta

\]

The second term can be rewritten as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = \frac{\nabla_\theta Z_\theta}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\nabla_\theta \int e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int \nabla_\theta e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int e^{-E_\theta(x)} \nabla_\theta (-E_\theta(x)) dx}{Z_\theta} = -\int \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x) dx

\]

Thus,

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = -\mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

Therefore, we can write the learning gradient as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

We can separate the loss into two phases of learning called positive and negative

. The positive phase consists of minimizing the energy of points drawn from $ p_{data} $

and is straightforward to compute assuming that $ E_θ(x) $ is differentiable (like a CNN). This has the effect of making the data points more likely (i.e., push down on their energy). However, this alone would lead to a flat energy landscape (i.e., 0 everywhere).

To counteract this, the negative phase pushes up on the energy of points drawn from the model distribution $ p_θ $

: the energy of the points that are unlikely in $ p_{data} $ will only get pushed up while those that are likely are going to get balanced out by the positive phase and will stay relatively low. It is the balancing of these two forces that shapes the energy landscape:

*Fitting a max likelihood energy model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p476*

Step2 of generative modeling: generate new data that fit the original data distribution

Once we have a model that correctly models the data distribution, we can generate new ”imagined” data points by starting a sampling chain at a random point (i.e. random noise for images) and let it drop to a low-energy point (i.e. an image most alike training data) or to high probability points

.

Generative models operate in a "one-to-many

" fashion, meaning that a single input can lead to multiple possible outputs. For example, if you input the same sentence into a text generation model, it could generate several different responses. So there is no single correct or predetermined answer for a given input. This introduces uncertainty that needs to be handled.

Thus, the generator must be stochastic

, meaning that it should incorporate elements of randomness. Thus, for the same input, a stochastic generator can produce different outputs each time it is executed. So we do not only need to build a generator that fit the original data distribution, but we also need to build a stochastic generator. How to do so?

- **The Diffusion models way:** A common method to make a stochastic generator is by using stochastic inputs

. This means that while the function itself is deterministic (producing the same output for the same input), it can produce varied results if the input is random. In other words, the generator would be $ generator(z, y) = x $ with $ z $ a randomized vector. In the case of image generation, if we give the generator as input "dog", it will generate an image of a dog, and this latent vector $ z $ will specify exactly which dog to generate

(breed, size, color, background, ...). $ z $ is called a "vector of latent variables" because the variables are not directly observed in the training data (it is also called "noise").

The function can output a different image $ x $ for each different setting of $ z $. Usually, we draw $ z $ from a simple distribution of Gaussian noise, that is, $ z∼N(0,1) $. $ G: Z, Y → X $

- **The Transformers way:** Transformers use the temperature parameter

or other sampling-based techniques

to manage ambiguity in text generation. The next token prediction in Autoregressive Transformers models is inherently a deterministic function; the same probability is assigned to the next tokens. During inference, greedy decoding (choosing the token with the highest probability at each step) keeps no randomness, whereas using sampling-based techniques like top-k sampling or nucleus (top-p) sampling, tokens are chosen randomly according to their probabilities, introducing randomness

into the generation process. The Temperature parameter scaling can also introduce stochasticity by altering the model's probability distribution over the next token.

I have based my writings on my comprehension of

*[Foundations of Computer Vision book from Antonio Torralba et al.](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), [Léo Gagnon et al's paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.12176) and [Andy Jones's post](https://andrewcharlesjones.github.io/journal/ebms.html)*

Therefore, other methods have emerged that are more "data-driven", which do not require full model specification from the start but focus solely on the data

(with few to no assumptions about the function to be learned to represent the data).

One of these methods for generative modeling is the Energy-Based modeling

. Energy-Based models flexibly model probability distributions

and have risen in popularity recently thanks to the impressive results obtained in image generation by parameterizing the distribution with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN).

Model the data distribution: first step of generative modeling

Learning statistical models of observational data has always been one of the primary goals in machine learning and more generally in statistics.

Density models

Density models are models that learn the probability density function (PDF) $ p_θ $ of the data, assuming that the data follows a probability density function.

Why using density functions to describe the data? Because density functions provide a mathematically rigorous way to describe the distribution of continuous random variables.

Density functions are normalized, meaning the total probability over all possible outcomes is 1: Density functions give high values to regions where there is lot of observed data, and low values to regions where there is few or no observed data, since it is a probability (sum of all values equal to 1).

This ensures that the probabilities are meaningful and consistent.

Energy-Based Models

Energy-Based Models emerged to tackle the assumption that the function to be learned is normalizable (because it is not always the case)

. Energy-Based Models exploit probability distributions only defined though unnormalized scores.

The approach is still to find $ p'_θ $ which we think is a good approximation of the real data distribution. Since $ p'_θ $ is unnormalized, $ p_θ(x) = p'_θ(x) / Z_θ $, so it is easy to go back to a normalized density function

(we just need to multiply by $ Z_θ $). This is why energy functions can do most of what probability densities can do (mathematically speaking), except that they do not give normalized probabilities.

In Energy-Based Models, $ p'_θ(x) = e^{-E_θ(x)}$, and $ E_θ $ is what we call the energy function

. $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ associates a scalar measure of incompatibility to each data point.

The $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ distribution comes from statistical physics

: Considering physical systems containing multiple particles, with a specific temperature, each particle has an energy associated with itself (kinetic energy, which is related to the movement of the particle, and potential energy, which is related to the interactions between the particles or with external fields).

The Boltzmann-Gibbs probability distribution describes the likelihood of a system being in a particular state based on the total energy of that state (of all particules) and the temperature of the system

. In this context, the state $ x $ of a system refers to a specific configuration of the positions of all particles within the system. For example, if we have $ n $ particles, then $ x $ is a vector $ [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n] $, where each $ x_i $ represents the position of the $ i $-th particle.

The energy $ E(x) $ of this state is a function of the positions of all particles.

The Boltzmann-Gibbs distribution $ p(x) $, providing the probability that the system is in a specific configuration $ x $, is given by the formula: \( p(x) = \frac{\exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\}}{Z} \)

where $ T$ is the temperature of the system, and \( Z = \int_{X^2} \exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\} dx \) is a normalizing constant that makes the distribution sum to one.

The probability $ p(x) $ describes the relative frequency at which the system is found in the state $ x $

. If we suppose that x is a one-dimensional state:

If we take a low temperature ( $ T = 1.6 $ ), we get:

Note that the normalized density is $ p(x) $. We see that states with lower energy $ E(x) $ are more probable, especially at low temperatures. Conversely, higher energy states are less probable.

Energy values reacts on the opposite of the density points: in probability density, there is a high value where there are lot of data and a low value where there is few data. It is actually the opposite for energy values: Lower energy values correspond to higher probability (more likely) data points, while higher energy values correspond to lower probability (less likely) data points

.

$ E_θ $ is actually part of the normalized density formula (it is part of the exponential form of the probability density function): \( p_\theta = e^{-\frac{E_\theta}{Z(\theta)}} \) where $ Z(θ) $ is the normalizing constant: \( Z(\theta) = \int_x e^{-E_\theta(x)} \, dx \)

.

Comparison of the loss and gradient formula

**The Kullback-Leibler (KL) loss : maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data**

use the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence as loss function

(to measure the distance between $ p_θ $ and $ p_{data} $): \( \arg \min_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}} \left[ -\log \frac{p_\theta(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x)} \right] = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_{\text{data}}(x)] \) \( = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] \) (since the second term has no dependence on $ p_θ $), which is almost equal to \( \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \log(p_\theta(x_i)) \), which is the maximum likelihood formula.

Therefore, it boils down to a form of maximum likelihood learning: the process of fitting the model to the data involves maximizing the likelihood of the observed data under the model (adjusting the parameters of the model so that it assigns the highest possible probability to the training data).

Let us see what happens when we try to learn the parameters of a model with maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data.

**1) For an Density Model:**

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

For a probability density function \( p_\theta(x) \):

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

Computing the gradient gives:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta \log p_\theta(x)]

\]

It comes down to pushing up the density over certain datapoints as presented in the figure in green

), we are forced to sacrifice the density over other regions

and pushing down the density over other datapoints as presented in the figure in red

:

*Fitting a max likelihood density model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p475*

**2) For an Energy-Based Model:**

For an Energy-Based Model (EBM), the probability density is often expressed in terms of an energy function $ E_\theta(x) $:

\[

p_\theta(x) = \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta}

\]

where \( Z_\theta \) is the partition function:

\[

Z_\theta = \int e^{-E_\theta(x')} dx'

\]

Thus, the negative log-likelihood becomes:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)] = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} \left[ \log \left( \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \right) \right]

\]

Simplifying this, we get:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [E_\theta(x)] + \log Z_\theta

\]

Computing the gradient of this function:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] + \nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta

\]

The second term can be rewritten as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = \frac{\nabla_\theta Z_\theta}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\nabla_\theta \int e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int \nabla_\theta e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int e^{-E_\theta(x)} \nabla_\theta (-E_\theta(x)) dx}{Z_\theta} = -\int \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x) dx

\]

Thus,

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = -\mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

Therefore, we can write the learning gradient as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

We can separate the loss into two phases of learning called positive and negative

. The positive phase consists of minimizing the energy of points drawn from $ p_{data} $

and is straightforward to compute assuming that $ E_θ(x) $ is differentiable (like a CNN). This has the effect of making the data points more likely (i.e., push down on their energy). However, this alone would lead to a flat energy landscape (i.e., 0 everywhere).

To counteract this, the negative phase pushes up on the energy of points drawn from the model distribution $ p_θ $

: the energy of the points that are unlikely in $ p_{data} $ will only get pushed up while those that are likely are going to get balanced out by the positive phase and will stay relatively low. It is the balancing of these two forces that shapes the energy landscape:

*Fitting a max likelihood energy model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p476*

Step2 of generative modeling: generate new data that fit the original data distribution

Once we have a model that correctly models the data distribution, we can generate new ”imagined” data points by starting a sampling chain at a random point (i.e. random noise for images) and let it drop to a low-energy point (i.e. an image most alike training data) or to high probability points

.

Generative models operate in a "one-to-many

" fashion, meaning that a single input can lead to multiple possible outputs. For example, if you input the same sentence into a text generation model, it could generate several different responses. So there is no single correct or predetermined answer for a given input. This introduces uncertainty that needs to be handled.

Thus, the generator must be stochastic

, meaning that it should incorporate elements of randomness. Thus, for the same input, a stochastic generator can produce different outputs each time it is executed. So we do not only need to build a generator that fit the original data distribution, but we also need to build a stochastic generator. How to do so?

- **The Diffusion models way:** A common method to make a stochastic generator is by using stochastic inputs

. This means that while the function itself is deterministic (producing the same output for the same input), it can produce varied results if the input is random. In other words, the generator would be $ generator(z, y) = x $ with $ z $ a randomized vector. In the case of image generation, if we give the generator as input "dog", it will generate an image of a dog, and this latent vector $ z $ will specify exactly which dog to generate

(breed, size, color, background, ...). $ z $ is called a "vector of latent variables" because the variables are not directly observed in the training data (it is also called "noise").

The function can output a different image $ x $ for each different setting of $ z $. Usually, we draw $ z $ from a simple distribution of Gaussian noise, that is, $ z∼N(0,1) $. $ G: Z, Y → X $

- **The Transformers way:** Transformers use the temperature parameter

or other sampling-based techniques

to manage ambiguity in text generation. The next token prediction in Autoregressive Transformers models is inherently a deterministic function; the same probability is assigned to the next tokens. During inference, greedy decoding (choosing the token with the highest probability at each step) keeps no randomness, whereas using sampling-based techniques like top-k sampling or nucleus (top-p) sampling, tokens are chosen randomly according to their probabilities, introducing randomness

into the generation process. The Temperature parameter scaling can also introduce stochasticity by altering the model's probability distribution over the next token.

I have based my writings on my comprehension of

*[Foundations of Computer Vision book from Antonio Torralba et al.](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), [Léo Gagnon et al's paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.12176) and [Andy Jones's post](https://andrewcharlesjones.github.io/journal/ebms.html)*

, p475](/reflexions/generative_models/end_autoregressive_models/density_models.png) Therefore, other methods have emerged that are more "data-driven", which do not require full model specification from the start but focus solely on the data

(with few to no assumptions about the function to be learned to represent the data).

One of these methods for generative modeling is the Energy-Based modeling

. Energy-Based models flexibly model probability distributions

and have risen in popularity recently thanks to the impressive results obtained in image generation by parameterizing the distribution with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN).

Model the data distribution: first step of generative modeling

Learning statistical models of observational data has always been one of the primary goals in machine learning and more generally in statistics.

Density models

Density models are models that learn the probability density function (PDF) $ p_θ $ of the data, assuming that the data follows a probability density function.

Why using density functions to describe the data? Because density functions provide a mathematically rigorous way to describe the distribution of continuous random variables.

Density functions are normalized, meaning the total probability over all possible outcomes is 1: Density functions give high values to regions where there is lot of observed data, and low values to regions where there is few or no observed data, since it is a probability (sum of all values equal to 1).

This ensures that the probabilities are meaningful and consistent.

Energy-Based Models

Energy-Based Models emerged to tackle the assumption that the function to be learned is normalizable (because it is not always the case)

. Energy-Based Models exploit probability distributions only defined though unnormalized scores.

The approach is still to find $ p'_θ $ which we think is a good approximation of the real data distribution. Since $ p'_θ $ is unnormalized, $ p_θ(x) = p'_θ(x) / Z_θ $, so it is easy to go back to a normalized density function

(we just need to multiply by $ Z_θ $). This is why energy functions can do most of what probability densities can do (mathematically speaking), except that they do not give normalized probabilities.

In Energy-Based Models, $ p'_θ(x) = e^{-E_θ(x)}$, and $ E_θ $ is what we call the energy function

. $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ associates a scalar measure of incompatibility to each data point.

The $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ distribution comes from statistical physics

: Considering physical systems containing multiple particles, with a specific temperature, each particle has an energy associated with itself (kinetic energy, which is related to the movement of the particle, and potential energy, which is related to the interactions between the particles or with external fields).

The Boltzmann-Gibbs probability distribution describes the likelihood of a system being in a particular state based on the total energy of that state (of all particules) and the temperature of the system

. In this context, the state $ x $ of a system refers to a specific configuration of the positions of all particles within the system. For example, if we have $ n $ particles, then $ x $ is a vector $ [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n] $, where each $ x_i $ represents the position of the $ i $-th particle.

The energy $ E(x) $ of this state is a function of the positions of all particles.

The Boltzmann-Gibbs distribution $ p(x) $, providing the probability that the system is in a specific configuration $ x $, is given by the formula: \( p(x) = \frac{\exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\}}{Z} \)

where $ T$ is the temperature of the system, and \( Z = \int_{X^2} \exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\} dx \) is a normalizing constant that makes the distribution sum to one.

The probability $ p(x) $ describes the relative frequency at which the system is found in the state $ x $

. If we suppose that x is a one-dimensional state:

If we take a low temperature ( $ T = 1.6 $ ), we get:

Note that the normalized density is $ p(x) $. We see that states with lower energy $ E(x) $ are more probable, especially at low temperatures. Conversely, higher energy states are less probable.

Energy values reacts on the opposite of the density points: in probability density, there is a high value where there are lot of data and a low value where there is few data. It is actually the opposite for energy values: Lower energy values correspond to higher probability (more likely) data points, while higher energy values correspond to lower probability (less likely) data points

.

$ E_θ $ is actually part of the normalized density formula (it is part of the exponential form of the probability density function): \( p_\theta = e^{-\frac{E_\theta}{Z(\theta)}} \) where $ Z(θ) $ is the normalizing constant: \( Z(\theta) = \int_x e^{-E_\theta(x)} \, dx \)

.

Comparison of the loss and gradient formula

**The Kullback-Leibler (KL) loss : maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data**

use the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence as loss function

(to measure the distance between $ p_θ $ and $ p_{data} $): \( \arg \min_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}} \left[ -\log \frac{p_\theta(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x)} \right] = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_{\text{data}}(x)] \) \( = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] \) (since the second term has no dependence on $ p_θ $), which is almost equal to \( \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \log(p_\theta(x_i)) \), which is the maximum likelihood formula.

Therefore, it boils down to a form of maximum likelihood learning: the process of fitting the model to the data involves maximizing the likelihood of the observed data under the model (adjusting the parameters of the model so that it assigns the highest possible probability to the training data).

Let us see what happens when we try to learn the parameters of a model with maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data.

**1) For an Density Model:**

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

For a probability density function \( p_\theta(x) \):

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

Computing the gradient gives:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta \log p_\theta(x)]

\]

It comes down to pushing up the density over certain datapoints as presented in the figure in green

), we are forced to sacrifice the density over other regions

and pushing down the density over other datapoints as presented in the figure in red

:

*Fitting a max likelihood density model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p475*

**2) For an Energy-Based Model:**

For an Energy-Based Model (EBM), the probability density is often expressed in terms of an energy function $ E_\theta(x) $:

\[

p_\theta(x) = \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta}

\]

where \( Z_\theta \) is the partition function:

\[

Z_\theta = \int e^{-E_\theta(x')} dx'

\]

Thus, the negative log-likelihood becomes:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)] = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} \left[ \log \left( \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \right) \right]

\]

Simplifying this, we get:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [E_\theta(x)] + \log Z_\theta

\]

Computing the gradient of this function:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] + \nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta

\]

The second term can be rewritten as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = \frac{\nabla_\theta Z_\theta}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\nabla_\theta \int e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int \nabla_\theta e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int e^{-E_\theta(x)} \nabla_\theta (-E_\theta(x)) dx}{Z_\theta} = -\int \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x) dx

\]

Thus,

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = -\mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

Therefore, we can write the learning gradient as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

We can separate the loss into two phases of learning called positive and negative

. The positive phase consists of minimizing the energy of points drawn from $ p_{data} $

and is straightforward to compute assuming that $ E_θ(x) $ is differentiable (like a CNN). This has the effect of making the data points more likely (i.e., push down on their energy). However, this alone would lead to a flat energy landscape (i.e., 0 everywhere).

To counteract this, the negative phase pushes up on the energy of points drawn from the model distribution $ p_θ $

: the energy of the points that are unlikely in $ p_{data} $ will only get pushed up while those that are likely are going to get balanced out by the positive phase and will stay relatively low. It is the balancing of these two forces that shapes the energy landscape:

*Fitting a max likelihood energy model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p476*

Step2 of generative modeling: generate new data that fit the original data distribution

Once we have a model that correctly models the data distribution, we can generate new ”imagined” data points by starting a sampling chain at a random point (i.e. random noise for images) and let it drop to a low-energy point (i.e. an image most alike training data) or to high probability points

.

Generative models operate in a "one-to-many

" fashion, meaning that a single input can lead to multiple possible outputs. For example, if you input the same sentence into a text generation model, it could generate several different responses. So there is no single correct or predetermined answer for a given input. This introduces uncertainty that needs to be handled.

Thus, the generator must be stochastic

, meaning that it should incorporate elements of randomness. Thus, for the same input, a stochastic generator can produce different outputs each time it is executed. So we do not only need to build a generator that fit the original data distribution, but we also need to build a stochastic generator. How to do so?

- **The Diffusion models way:** A common method to make a stochastic generator is by using stochastic inputs

. This means that while the function itself is deterministic (producing the same output for the same input), it can produce varied results if the input is random. In other words, the generator would be $ generator(z, y) = x $ with $ z $ a randomized vector. In the case of image generation, if we give the generator as input "dog", it will generate an image of a dog, and this latent vector $ z $ will specify exactly which dog to generate

(breed, size, color, background, ...). $ z $ is called a "vector of latent variables" because the variables are not directly observed in the training data (it is also called "noise").

The function can output a different image $ x $ for each different setting of $ z $. Usually, we draw $ z $ from a simple distribution of Gaussian noise, that is, $ z∼N(0,1) $. $ G: Z, Y → X $

- **The Transformers way:** Transformers use the temperature parameter

or other sampling-based techniques

to manage ambiguity in text generation. The next token prediction in Autoregressive Transformers models is inherently a deterministic function; the same probability is assigned to the next tokens. During inference, greedy decoding (choosing the token with the highest probability at each step) keeps no randomness, whereas using sampling-based techniques like top-k sampling or nucleus (top-p) sampling, tokens are chosen randomly according to their probabilities, introducing randomness

into the generation process. The Temperature parameter scaling can also introduce stochasticity by altering the model's probability distribution over the next token.

I have based my writings on my comprehension of

*[Foundations of Computer Vision book from Antonio Torralba et al.](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), [Léo Gagnon et al's paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.12176) and [Andy Jones's post](https://andrewcharlesjones.github.io/journal/ebms.html)*

Therefore, other methods have emerged that are more "data-driven", which do not require full model specification from the start but focus solely on the data

(with few to no assumptions about the function to be learned to represent the data).

One of these methods for generative modeling is the Energy-Based modeling

. Energy-Based models flexibly model probability distributions

and have risen in popularity recently thanks to the impressive results obtained in image generation by parameterizing the distribution with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN).

Model the data distribution: first step of generative modeling

Learning statistical models of observational data has always been one of the primary goals in machine learning and more generally in statistics.

Density models

Density models are models that learn the probability density function (PDF) $ p_θ $ of the data, assuming that the data follows a probability density function.

Why using density functions to describe the data? Because density functions provide a mathematically rigorous way to describe the distribution of continuous random variables.

Density functions are normalized, meaning the total probability over all possible outcomes is 1: Density functions give high values to regions where there is lot of observed data, and low values to regions where there is few or no observed data, since it is a probability (sum of all values equal to 1).

This ensures that the probabilities are meaningful and consistent.

Energy-Based Models

Energy-Based Models emerged to tackle the assumption that the function to be learned is normalizable (because it is not always the case)

. Energy-Based Models exploit probability distributions only defined though unnormalized scores.

The approach is still to find $ p'_θ $ which we think is a good approximation of the real data distribution. Since $ p'_θ $ is unnormalized, $ p_θ(x) = p'_θ(x) / Z_θ $, so it is easy to go back to a normalized density function

(we just need to multiply by $ Z_θ $). This is why energy functions can do most of what probability densities can do (mathematically speaking), except that they do not give normalized probabilities.

In Energy-Based Models, $ p'_θ(x) = e^{-E_θ(x)}$, and $ E_θ $ is what we call the energy function

. $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ associates a scalar measure of incompatibility to each data point.

The $ E_θ(x) > 0 $ distribution comes from statistical physics

: Considering physical systems containing multiple particles, with a specific temperature, each particle has an energy associated with itself (kinetic energy, which is related to the movement of the particle, and potential energy, which is related to the interactions between the particles or with external fields).

The Boltzmann-Gibbs probability distribution describes the likelihood of a system being in a particular state based on the total energy of that state (of all particules) and the temperature of the system

. In this context, the state $ x $ of a system refers to a specific configuration of the positions of all particles within the system. For example, if we have $ n $ particles, then $ x $ is a vector $ [x_1, x_2, ..., x_n] $, where each $ x_i $ represents the position of the $ i $-th particle.

The energy $ E(x) $ of this state is a function of the positions of all particles.

The Boltzmann-Gibbs distribution $ p(x) $, providing the probability that the system is in a specific configuration $ x $, is given by the formula: \( p(x) = \frac{\exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\}}{Z} \)

where $ T$ is the temperature of the system, and \( Z = \int_{X^2} \exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{T} E(x) \right\} dx \) is a normalizing constant that makes the distribution sum to one.

The probability $ p(x) $ describes the relative frequency at which the system is found in the state $ x $

. If we suppose that x is a one-dimensional state:

If we take a low temperature ( $ T = 1.6 $ ), we get:

Note that the normalized density is $ p(x) $. We see that states with lower energy $ E(x) $ are more probable, especially at low temperatures. Conversely, higher energy states are less probable.

Energy values reacts on the opposite of the density points: in probability density, there is a high value where there are lot of data and a low value where there is few data. It is actually the opposite for energy values: Lower energy values correspond to higher probability (more likely) data points, while higher energy values correspond to lower probability (less likely) data points

.

$ E_θ $ is actually part of the normalized density formula (it is part of the exponential form of the probability density function): \( p_\theta = e^{-\frac{E_\theta}{Z(\theta)}} \) where $ Z(θ) $ is the normalizing constant: \( Z(\theta) = \int_x e^{-E_\theta(x)} \, dx \)

.

Comparison of the loss and gradient formula

**The Kullback-Leibler (KL) loss : maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data**

use the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence as loss function

(to measure the distance between $ p_θ $ and $ p_{data} $): \( \arg \min_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}} \left[ -\log \frac{p_\theta(x)}{p_{\text{data}}(x)} \right] = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_{\text{data}}(x)] \) \( = \arg \max_{p_\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log p_\theta(x)] \) (since the second term has no dependence on $ p_θ $), which is almost equal to \( \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \log(p_\theta(x_i)) \), which is the maximum likelihood formula.

Therefore, it boils down to a form of maximum likelihood learning: the process of fitting the model to the data involves maximizing the likelihood of the observed data under the model (adjusting the parameters of the model so that it assigns the highest possible probability to the training data).

Let us see what happens when we try to learn the parameters of a model with maximum likelihood estimation, i.e., minimizing the expected negative log-likelihood of the data.

**1) For an Density Model:**

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

For a probability density function \( p_\theta(x) \):

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)]

\]

Computing the gradient gives:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta \log p_\theta(x)]

\]

It comes down to pushing up the density over certain datapoints as presented in the figure in green

), we are forced to sacrifice the density over other regions

and pushing down the density over other datapoints as presented in the figure in red

:

*Fitting a max likelihood density model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p475*

**2) For an Energy-Based Model:**

For an Energy-Based Model (EBM), the probability density is often expressed in terms of an energy function $ E_\theta(x) $:

\[

p_\theta(x) = \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta}

\]

where \( Z_\theta \) is the partition function:

\[

Z_\theta = \int e^{-E_\theta(x')} dx'

\]

Thus, the negative log-likelihood becomes:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\log p_\theta(x)] = -\mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} \left[ \log \left( \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \right) \right]

\]

Simplifying this, we get:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [E_\theta(x)] + \log Z_\theta

\]

Computing the gradient of this function:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] + \nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta

\]

The second term can be rewritten as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = \frac{\nabla_\theta Z_\theta}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\nabla_\theta \int e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int \nabla_\theta e^{-E_\theta(x)} dx}{Z_\theta} = \frac{\int e^{-E_\theta(x)} \nabla_\theta (-E_\theta(x)) dx}{Z_\theta} = -\int \frac{e^{-E_\theta(x)}}{Z_\theta} \nabla_\theta E_\theta(x) dx

\]

Thus,

\[

\nabla_\theta \log Z_\theta = -\mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

Therefore, we can write the learning gradient as:

\[

\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}_{\text{NLL}} = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}}} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)] - \mathbb{E}_{p_\theta} [\nabla_\theta E_\theta(x)]

\]

We can separate the loss into two phases of learning called positive and negative

. The positive phase consists of minimizing the energy of points drawn from $ p_{data} $

and is straightforward to compute assuming that $ E_θ(x) $ is differentiable (like a CNN). This has the effect of making the data points more likely (i.e., push down on their energy). However, this alone would lead to a flat energy landscape (i.e., 0 everywhere).

To counteract this, the negative phase pushes up on the energy of points drawn from the model distribution $ p_θ $

: the energy of the points that are unlikely in $ p_{data} $ will only get pushed up while those that are likely are going to get balanced out by the positive phase and will stay relatively low. It is the balancing of these two forces that shapes the energy landscape:

*Fitting a max likelihood energy model to data, from [Antonio Torralba et al.'s book](https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262048972/foundations-of-computer-vision/), p476*

Step2 of generative modeling: generate new data that fit the original data distribution

Once we have a model that correctly models the data distribution, we can generate new ”imagined” data points by starting a sampling chain at a random point (i.e. random noise for images) and let it drop to a low-energy point (i.e. an image most alike training data) or to high probability points

.

Generative models operate in a "one-to-many

" fashion, meaning that a single input can lead to multiple possible outputs. For example, if you input the same sentence into a text generation model, it could generate several different responses. So there is no single correct or predetermined answer for a given input. This introduces uncertainty that needs to be handled.

Thus, the generator must be stochastic

, meaning that it should incorporate elements of randomness. Thus, for the same input, a stochastic generator can produce different outputs each time it is executed. So we do not only need to build a generator that fit the original data distribution, but we also need to build a stochastic generator. How to do so?

- **The Diffusion models way:** A common method to make a stochastic generator is by using stochastic inputs

. This means that while the function itself is deterministic (producing the same output for the same input), it can produce varied results if the input is random. In other words, the generator would be $ generator(z, y) = x $ with $ z $ a randomized vector. In the case of image generation, if we give the generator as input "dog", it will generate an image of a dog, and this latent vector $ z $ will specify exactly which dog to generate

(breed, size, color, background, ...). $ z $ is called a "vector of latent variables" because the variables are not directly observed in the training data (it is also called "noise").

The function can output a different image $ x $ for each different setting of $ z $. Usually, we draw $ z $ from a simple distribution of Gaussian noise, that is, $ z∼N(0,1) $. $ G: Z, Y → X $

- **The Transformers way:** Transformers use the temperature parameter

or other sampling-based techniques

to manage ambiguity in text generation. The next token prediction in Autoregressive Transformers models is inherently a deterministic function; the same probability is assigned to the next tokens. During inference, greedy decoding (choosing the token with the highest probability at each step) keeps no randomness, whereas using sampling-based techniques like top-k sampling or nucleus (top-p) sampling, tokens are chosen randomly according to their probabilities, introducing randomness